How to Become a Ming Furniture Maker by Accident: A Student’s Path into Chinese Furniture

By Hugo Nakashima-Brown

Hugo Nakashima-Brown makes bespoke furniture in Boston and teaches at RISD.

I got into woodworking almost by accident. I had moved to South Korea for a relationship and left behind my painting career in New York to work at a gallery in Seoul. On my way back to the States, relatives with a long-standing furniture business offered me a design job. I'd always been drawn to wood, though my only real experience was making canvas stretchers. I even gave away my set of Marples chisels before Korea as part of a Marie Kondo purge of unused objects.

From day one, I loved designing around wood. It combined my interest in architecture with studio-scale control. After two years, I left the family business to start my own practice and enrolled at North Bennet Street School in Boston to study period furniture making. I had two months before the program started, and my aunt and uncle offered me a place to stay near Delhi, NY. I set up shop in their unheated shed and spent that winter teaching myself to sharpen and cut dovetails by hand.

With an East Asian surname, I’d always been curious about non-Western furniture. But the realities of sitting—chairs, desks, beds—made it hard to take inspiration from floor-based traditions. Like many others, I found myself circling the Ming tradition, which looked strangely familiar—probably because of how much it influenced Western design, even if we don’t often talk about it that way. I had seen it in Gustav Ecke’s book and admired its almost modernist elegance, a bit like the Goryeo ceramics I loved in Seoul.

I chose North Bennet over places like Krenov or CFC because I wanted to unlearn some things. Having worked for a family business and grown up around that furniture, it felt important to rewire how I thought about design and joinery. Though I wasn’t drawn to Queen Anne pieces, the best work I saw from North Bennet students used period styles as a starting point, not a blueprint. It felt queerer, more fresh, less affected than the work I saw coming out of highly rated MFA programs.

That winter, I reached out to Andrew Hunter, whose studio I’d visited the year before through an introduction by the sculptor Martin Puryear. I had a small Japanese hand plane I didn’t know how to set up. Andrew kindly invited me to visit his studio before a Kezurokai event he and Suzanne Walton of Rowan Woodwork were organizing.

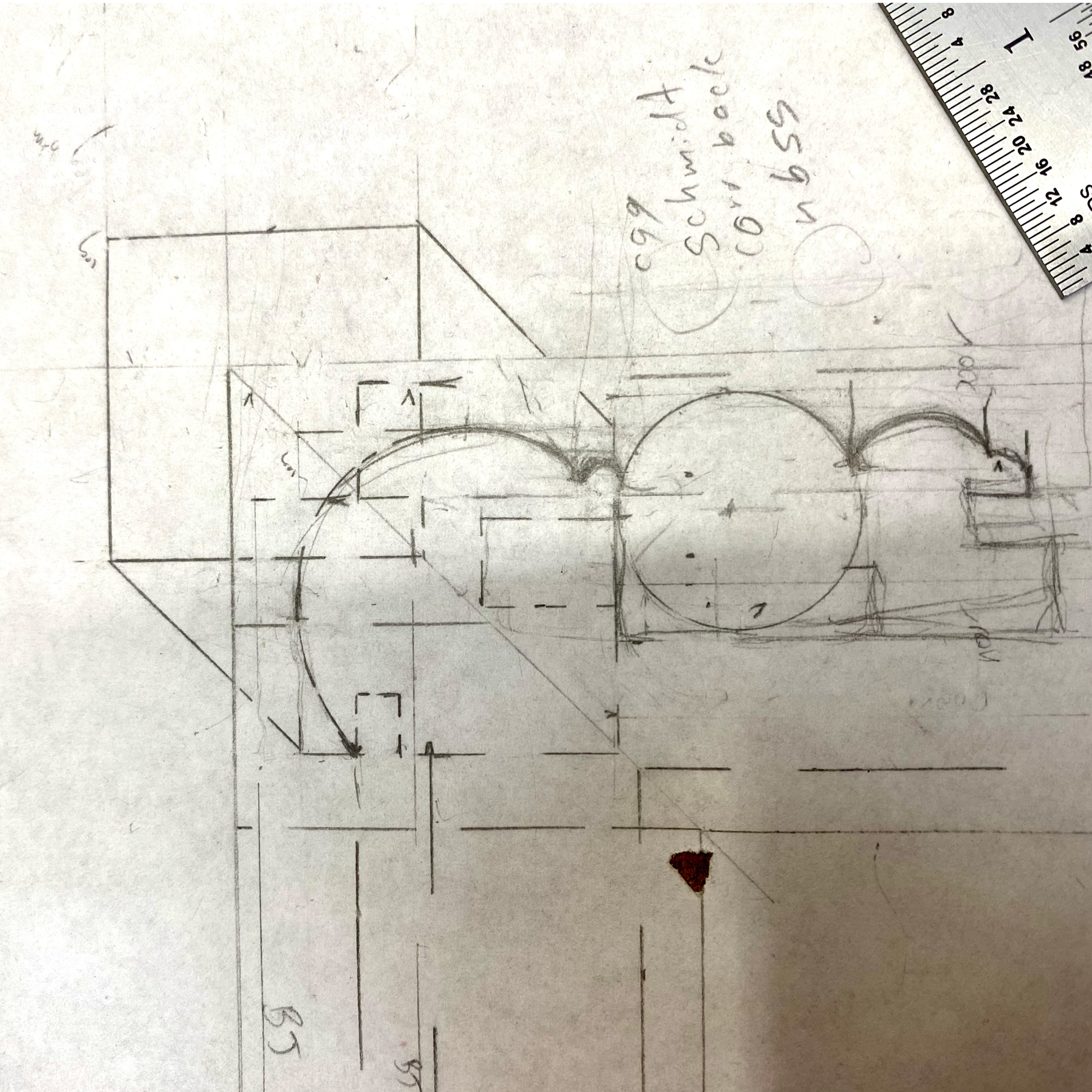

Spending the day in his shop, I found it hard to conceptualize layout or construction of joint samples like the three-way mitre used in a Ming sofa corner or a table joint with its mitered bridle. I couldn’t imagine making a piece of Ming furniture if this was the dedication required. It felt like something only possible at a time when people worked by hand every day and had the skills learned through access to only the most rudimentary of tools—when fitting something with a compound angle was no more difficult than cutting it square. I did manage to get my hand plane sharpened and tuned though (if poorly, as I look back at my heavy handed sharpening towards the back of the ura). It pulled a shaving, if not an especially thin one, on hard maple and left a smooth surface.

At North Bennet, I worked through the curriculum quickly and began side projects—including a bookshelf inspired by a Joseon-period Korean piece. In many ways the traditionalist school discouraged initiative, but students who went beyond the four required pieces found it paid off. I ended up making more than that, and the mix of machine and hand work still shapes how I build it today. It was the kind of education that often felt frustrating day-to-day, but by the end of each semester you could see how far you’d come. Perhaps the school’s best tradition were the weekly lectures of Lance Patterson—extended musings of a lifelong woodworker with more curiosity than ego, whose values prioritized just getting by over chasing profit.

The more I looked at Western period furniture, the more I saw strong Chinese influence. Yet classroom discussions still circled around Western classical architecture, Euclidean geometry, and the “Orient” as exotic backdrop—more Cleopatra than cabinetmaking.

For our first independent design assignment—the Splay Leg table—I designed a desk based on a piece drawn in Gustav Ecke’s book. This was a good introduction to Chinese joinery, as there was only one truly unfamiliar joint—a sort of bridle joint with mitered decorative spandrels that not only added to the look of the piece but increased bearing (or, if desired, glue) surface.

I made a simple jig for the tablesaw for use with a flat-top blade to cut the joint—a piece of mdf glued to a baltic strip perfectly fitted into the saw track—both sides of the piece (for lefts and rights) were trimmed with the saw and blade to be used, providing a zero clearance reference that requisite angles could then be nailed on to, allowing you to use the tablesaw like a handsaw with guides, lining up your tickmarks or fixturing with stops.

I skipped the traditional mitered frame top and used a slab instead, as I like end grain. The wood was European beech with heartwood that looked cloud-like and cracks, patched with rosewood butterflies from another student’s scrap. Wood grows on trees, but it is easier to take risks when it costs $5.50 a board foot.

That table showed me how Ming joinery could push my growth. I wouldn’t have time for extensive R&D after school, so I dedicated my capstone pieces to Ming furniture. It was still period work—closer to the school’s ethos than contemporary design—and it pushed me, and sometimes my instructors. Since Ming work was originally built with basic hand tools, I challenged myself to find machine-based workflows.

My next major project was a yuanjiaogui, a round-corner cabinet with pivoting doors. Ecke’s drawing had errors, especially around the molding. The pivoting doors were tricky to resolve, since the drawing placed the pivot in the wrong spot.

I found a lead in The Journal of the Classical Chinese Furniture Society—a short-lived publication put out by a California cult called the Fellowship of Friends. They bought Ming antiques cheap, built academic cachet around them, then sold the collection in 1996 for $11 million. Their HQ looked more like a plantation rose garden than a museum of Chinese furniture, in fact a relic of the Fellowship’s prior enterprise in Renaissance painting. Still, the journal was a goldmine for those willing to do a little digging, and one photo of a disassembled cabinet from Fujian helped me reverse-engineer the pivot placement.

I ground custom cutters for the spindle moulder to shape the moldings, used old Cuban mahogany veneer from the school’s free pile, and bought Honduran mahogany from Lance at near-cherry prices. A jewelry student made the nickel silver hardware from my drawings.

I also built a small incense stand—a xiangji—to see how far machine-based Ming furniture could go. I used jigs from Jamey Pope and Lance’s proposed work for the MFA’s Chinese art wing: Destaco clamps for routing legs, a pin router for the sliding dovetail aprons, and a jig for the tiny mitered feet.

My final student piece was a roundback chair, the form I had most admired in Ecke’s book when I visited Andrew’s shop. It had posts that ran through the seat and scarf-jointed into the crest rail. At several points I got stuck—unable to picture the next step. I advise my students not to back themselves into a corner, but sometimes it can force you to see a too ambitious project through.

Now, most of my income comes from teaching. I want my students to find value in traditions outside the Western canon, without needing to do all the detective work I did. Chinese furniture doesn’t have to be an overbuilt curiosity for specialists. It can offer something practical: inspiration for glueless, fastener-less design, for flatpack joinery, even for packaging. In the next piece for Paklan, I’ll explore how this work evolved after school—and how much you can learn about anonymous makers through their work.