In the introduction to his essay The Development of the Folding Chair, Gustave Ecke writes about two modest folding chairs in the possession of Phillip II of Spain (1527-1598), which the King reputedly used as footrests. During Phillip’s time, the bent-back splat used on the chair was a foreign oddity, but to a later European would be taken for granted, eventually remembered as Spanish.

“In the 18th century, Chinese and European furniture significantly influenced each other. This was especially profound in the early part of the century, though examples appear as early as the 16th century. The more recognizable wave of Chinese influence—of a Rococo kind—emerged around 1750. The new furniture styles of the Queen Anne period in Britain and the U.S., which abandon traditional European architectural elements, are largely based on imported Chinese furniture or depictions of such furniture in imported ceramics.”

William Slomann noted this in a 1929 exhibition catalog on 18th-century Chinese furniture. Eighteenth-century English designers looked to China with admiration—so much so that George Edwards proclaimed it was time for Ancient and Modern Rome to now give place.

Yet today, you'd be hard pressed to find a contemporary expert on Queen Anne or Newport furniture who discusses Chinese influence at any length—much less a furniture maker. That was true even in Slomann’s and Ecke’s time. Slomann’s work was critically dismissed by English scholars, despite the clear admiration for Chinese designs shown by their 18th-century predecessors. Within just a few generations, enthusiasm for Chinese design shifted into a colonialist disdain—first treating Chinese culture as lesser, and then erasing its influence entirely except in the most overt “Chinoiserie” styles.

In 1934, Slomann published a three-part article series titled The Indian Period of European Furniture, in which he proposed that much 17th-century furniture attributed to English and Dutch makers was in fact Asian in origin. “For all practical purposes,” he wrote, “I believe it to be safe to consider all lacquer work found in Europe and dating from about 1600 and fairly far on in the century as having come from India, or from China and Japan.” This suggestion was met with bemusement.

Despite the wealth of contemporary scholarship on Chinese export porcelain, Chinese influence on Western furniture remains relatively understated. This gap became especially clear to me after graduating from North Bennet in 2024, when I attended a Maker/Creator Fellowship at the Winterthur museum in Delaware. Without access to a shop, I opted to use roughly 1/2 of my month doing research in the library and 1/2 doing design work in the fellows office upstairs. Pulling dozens of volumes from Winterthur’s stacks, I went through every publication of East Asian furniture in their collection, but also pulled volumes on English, Spanish, and Danish furniture. Scholarly work had been done—for example, by Nicholas Grindley on Queen Anne-period Chinese influences, and by Karina Corrigan, Wang Shixiang, and Nancy Berliner on Chinese export wares and domestic furniture traditions. But none of this research was conducted by furniture makers.

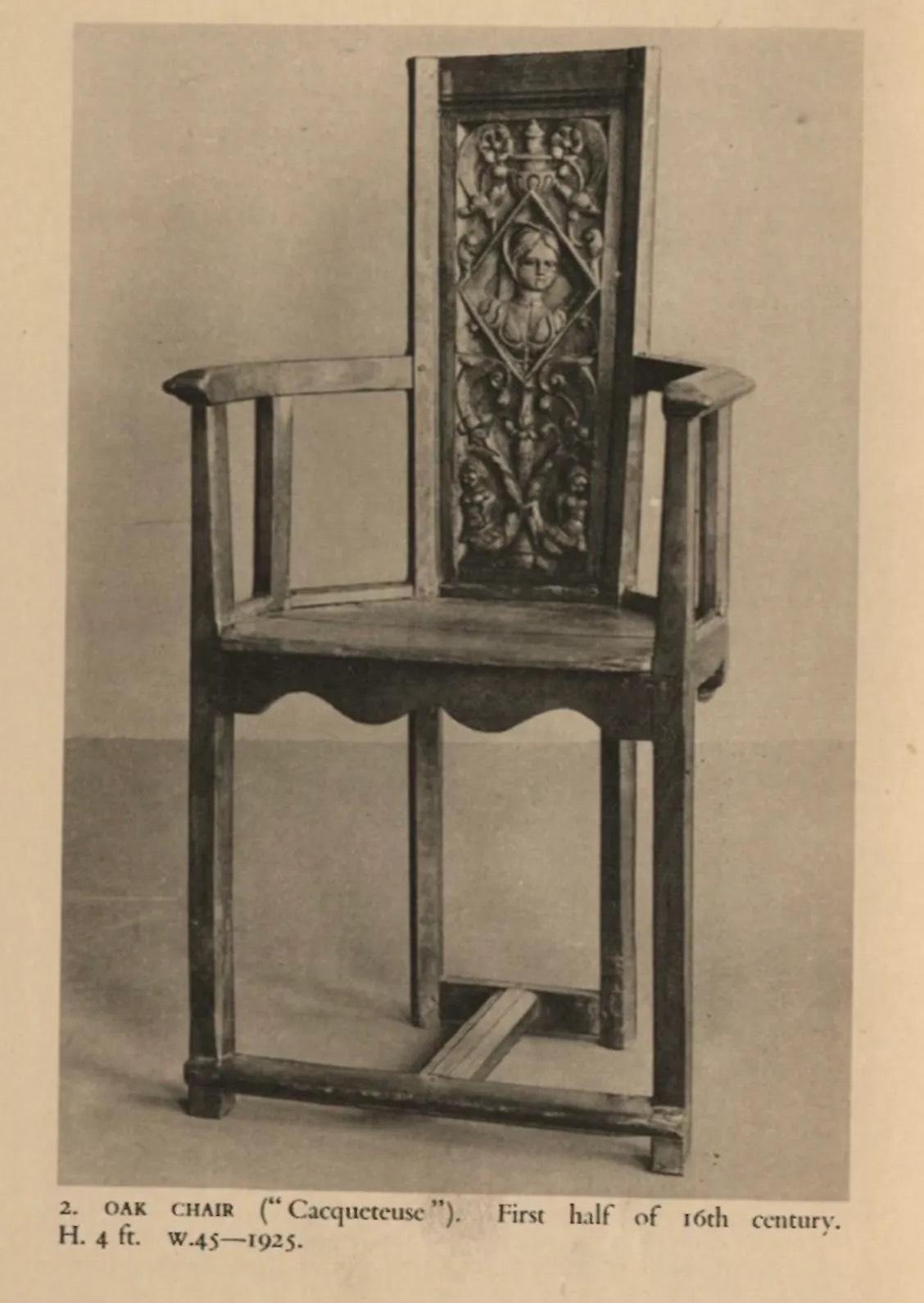

Flipping through a small red pamphlet entitled A Picture Book of English Chairs, published by the V&A in 1937, I came to a dead stop on only the second page.

This chair is usually attributed to being an English interpretation of a caquetoire, a French ladies armchair of the European Renaissance, literally a “chatting chair.” And while the general features were similar—round armrest, high back—that’s not what it most immediately reminded me of.

What is commonly believed to be the earliest example of Chinese influence in English furniture is a set of japanned chairs in Ham house from 1675. To my eyes, this chair, from over a century earlier, closely resembles the Ming style of the so-called Drunken Lord’s Chair. Sharing a bent back, round backed armrests with side spindles, distinctive undercarriage with coped shoulders around the legs, and Chinese-style ogee brackets—all read Chinese to me, not French or English. By contrast, a caquetorie generally has a trapezoidal seat and standard trapezoidal undercarriage flushed to the legs.

As someone who has made much Chinese furniture from photographs and old drawings, it does not look like the result of a cabinetmaker who had such a Ming chair in front of them. Rather, it looks like the result of a provincial English cabinetmaker trying to reproduce an image of a Chinese chair from a decorative object, relying on the joinery techniques they knew, however awkward the translation. Perhaps the local nobility had handed them a piece of China or imported lacquerware, already highly prized in England, and asked them to make such an exotic chair as depicted on the plate.

What’s fascinating is that by the 1730s, we also begin to see the reverse: Chinese artisans producing export furniture for the English market—furniture that they interpreted as English, based on English tastes for “Chinese furniture.” These pieces often blend structural languages. For example, a Queen Anne chair at the MFA Boston has a backsplat housed and pegged into the shoe with a pegged scarf joint connecting the back posts—techniques foreign to English makers of the time, but logical from the standpoint of a Chinese carpenter adapting to demand. Similarly, export casework often features mitered through-tenons, whereas a European maker would’ve used a blind tenon.

What’s most surprising is that despite well-documented influence—the bent back, the re-popularization of the cabriole leg, finials inspired by giant’s arm braces, even the ubiquitous scalloped aprons that only appear on English furniture after trade with China, I have yet to hear a period furniture maker talk about this influence. While we discuss its effect on mid-century Danish furniture like that of Wegner, we claim period furniture as uniquely our own, a spontaneous creation of Chippendale despite what they wrote in the introductions to their own books. I recently listened to a presentation on Greene and Greene furniture without a single mention of Chinese influence, only references to “cloud lifts” and “motifs of birds and flowers.” The speaker was unaware of the Chinese genre of bird and flower paintings.

[1] Slomann, Wilhelm. Eighteenth Century Chinese Furniture. 1929.

[2] Parker, George, and John Stalker. A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing. 1688.

[3] “Deep Innovation or Mere Eccentricity?” The Burlington Magazine Index Blog, 2014.

[4] Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. 1856.